Tag Archives: Sustainability

‘Triple Bottom Line’ Approach to Renewable Energy

Richard Ha writes:

We need a “triple bottom line” approach to renewable energy options. They need to be socially sustainable, environmentally sustainable, and economically sustainable.

World-renowned economist, Nobel laureate, and New York Times best-selling author Joseph Stiglitz spoke on this at UH Manoa. His lecture, “Where long-term and short-term goals converge: Using sustainability as an impetus for economic growth,” starts at the 21:30 mark of this video.

Social sustainability has largely been ignored in many approaches to renewable energy solutions. The Big Island has the lowest median family income in the state, and that is not socially sustainable. Hawaiians leaving their ancestral lands in greater and greater numbers in order to look for work is not socially sustainable.

We need to pay more attention to this. Finding solutions that give folks on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder more spending money will benefit all of us, because two-thirds of our economy is made up of consumer spending.

Energy and agriculture are inextricably tied together, and the agricultural industry is vulnerable because of its dependency on energy. Nitrogen fertilizer, plastics, chemicals, etc., are all byproducts of petroleum.

What can we do to dodge the bullet? We can maximize the resources we have available to us here in a sustainable way.

On the energy side, we have geothermal, which will be available to us, according to the scientists, for 500,000 years. On the ag side, we have a year-long growing season. These are both huge advantages. We need to leverage them so we have a competitive advantage over the rest of the world.

Geothermal electricity puts us on the right side of the cost curve. And as natural gas prices rise, we will be able to competitively make hydrogen. We can use that hydrogen for transportation, as well as to manufacture nitrogen fertilizer.

In the ag industry, we should be maximizing technology to help us with disease and insect control, thereby lessening our dependency on natural gas.

Our tourism industry is also at risk as jet fuel rises in cost. But with the same low-cost electricity that helps our farmers and their customers, we would lower the walk-around cost of the average tourist’s budget. This would both support our tourism industry and bring money into our local economy.

From Peak Oil News:

GEOG Researchers Address Economic Dangers of ‘Peak Oil’

Researchers from the University of Maryland and a leading university in Spain demonstrate in a new study which sectors could put the entire U.S. economy at risk when global oil production peaks (“Peak Oil”). This multi-disciplinary team recommends immediate action by government, private and commercial sectors to reduce the vulnerability of these sectors.

In the final analysis, we can no longer think and act in silence. We need a long-range systems approach, based on the three pillars of sustainability – social sustainability, environmental sustainability, and economic sustainability.

If you’d like to know more, sign up at the Big Island Community Coalition and we’ll send you an occasional email letting you know what we’re doing and how you can help.

[The link is not working from this blog, though the BICC website is up. Please go to www.bigislandcommunitycoalition.com.]

Non-GMO Cheerios a Non-Seller

Richard Ha writes:

Non-GMO Cheerios were recently unveiled with great expectation and anticipation, but the result? People did not flock to the stores. There was no increase in sales!

This does not surprise me. It is entirely consistent with the survey done by the Hawaii Rural Development Council, which found that Food Security is the most important sustainability issue in Hawaii. GMO didn’t even make the top three concerns, but came in at number five.

Hmmm.

The New Ahupuaa, Revisited

Richard Ha writes:

This is a post I wrote back in 2007. I recently reread it and realized it's the same story as what's happening today. It's six years later, and people still don't realize we don't have time to fool around.

I'm going to rerun the post here.

***

October 10, 2007

I spoke at the Hawai‘i Island Food Summit this past weekend, which was attended by Hawaiian cultural people, policy makers, university researchers, farmers, ranchers, and others.

The two-day conference asked the question, “How Can Hawai‘i Feed Itself?”

I felt like a small kid in class with his hand raised: “Call me! Call me!”

I sat on one of the panels, and said that our sustainability philosophy has to do with taking a long-term view of things. We are always moving so we’ll be in the proper position for the environment we anticipate five, 10 and 20 years from now.

I told them I had a nightmare that there would be a big meeting down by the pier one day, where they announce that food supplies were short because the oil supply was short and so we would have to send thousands of people out to discover new land.

I was afraid that they would send all the people with white hair out on the boats to find new land—all the Grandmas and Grandpas and me, but maybe not June.

Grandmas and Grandpas hobbled onto the boats with their canes and their wheelchairs, clutching all their medicines, and everybody gave all of us flower leis, and everyone was saying, “Aloha, Aloha, call us when you find land! Aloha!”

I spoke about where we want to be in five, 10 or 20 years. We know that energy-related costs will be high then. And that we need to provide food for Hawai‘i’s people.

We call our plan “The New Ahupua‘a.”

In old Hawai‘i, the ahupua‘a was a land division that stretched from the uplands to the sea, and it contained the resources necessary to support its human population—from fish and salt to fertile land for farming and, high up, wood for building, as well as much more.

Our “New Ahupua‘a” uses old knowledge along with modern technology to make the best use of our own land system and resources. We will move forward by looking backward.

• We plan to decouple ourselves from fossil fuel costs by developing a hydroelectric plant, which will allow us to grow various crops not normally grown at our location.

• We are moving toward a “village” concept of farming, and starting to include farmers from the area, who grow things we don’t, to farm with us. This way, the people who work on our farm come from the area around our farm. We will help them with food safety, pest control issues and distribution.

• We are developing a farmers market at our property on the highway, where the farmers who work with us can market their products.

• We will utilize as much of our own resources for fertilizer as possible, by developing a system of aquaponics, etc.

This “New Ahupua‘a” is our general framework for the future. It will allow us to produce more food than we can produce by ourselves. It is a safe strategy, in case the worst scenario happens; if it doesn’t, this plan will not hurt us.

It is a simple strategy. And we are committed to it.

My assessment of how we came to be here and where we need to be in the future is this: In the beginning, one hundred percent of the energy for food came from the sun. The mastodons ate leaves, the saber tooth tiger ate the mastodon and we ate the tiger and everything else.

The earth’s population was related to the amount of food we could gather or catch. And sometimes the food caught and ate us. So there were only so many of us roaming around.

Then some of us started to use horses and mules to help us grow food. As well as the sun, now animals provided some of the energy for cultivating food. We were able to grow more food, and so there were more of us.

About 150 years ago, we discovered oil. With oil we could utilize millions of horsepower to grow food—and we didn’t even need horses. Oil was plentiful and cheap; only about $3/barrel. We used oil to manufacture fertilizer, chemicals and for packaging and transportation.

Food became very, very plentiful and we started going to supermarkets to harvest and hunt for our food. Hunting for our food at the supermarkets was very good—the food did not eat us and now there are many, many, many of us.

But now we are approaching another change to the status quo—a situation being called “Peak Oil.” That’s when half of all the oil in existence is used up. Half the oil will still be left, but it will be increasingly hard to tap. At some point, the demand for oil—by billions and billions of people who cannot wait to get in their car and drive to McDonalds—will exceed the ability to pump that oil.

Food was cheap in the past because oil was cheap. Five years ago, oil was $30/barrel but now it’s over $80/barrel. Now that oil is becoming more and more expensive, food is also going to become much more expensive.

In the beginning the sun provided a hundred percent of the energy and it was free. Today oil is becoming very expensive, but sun energy is still free. The wind, the waves, the water—they are all free here in Hawaii. It’s the oil that is expensive.

For Hamakua Springs, the situation is not complicated at all. We need to use an alternate form of energy to help us grow food!

With alternate energy, we should be able to continue growing food—and maybe local food can be grown cheaper than food that is shipped here from far away.

I told the Food Summit attendees that we farmers need to grow plenty of food so that others can do what they do and so we continue to have a vibrant society. If we don’t plan ahead to provide enough food, and as a consequence every family has to return to farming to feed themselves, it would be a much more limited society. People would not be able to pursue the arts, write books, explore space. We would have way fewer choices – maybe only, “What color malo should I wear today?”

There was a feeling going through the Food Summit’s crowd that we were a part of something very important and very special. What I found different about this conference is that people left feeling that this was just the beginning.

We are going to take action.

***

State of the Farm Report

Richard Ha writes:

Yesterday at the farm I had a meeting with all our workers. It was an update on where we have been and where we are going.

Where we’ve been

The price of oil has quadrupled in the last 10 years, and those who could pass on the cost did. Those who could not pass on the cost ended up paying more. Farmers are price takers, not price makers, so farmers’ costs increased more than their prices.

Anticipating higher electricity prices, we lobbied for and passed a law that the Department of Agriculture create a new farm loan program that farmers could use for renewable energy purposes. Then we started to design a hydroelectricity program to stabilize our electricity costs.

Where we are today

The hydroelectricity project is within weeks of completion. With the combination of a farm loan and a grant from the Department of Energy, we will stabilize our electricity price at 40 percent less than we pay today.

The pipe that transports the water appears to me like it will last for more than 100 years. After the loan is paid off, our electricity will be practically free for more than 60 years.

Where we are going

We are taking advantage of our resources – free water and stable electricity costs – by working with area farmers to help each other grow more food.

What kind of food? Responding to consumer demand, we want to

produce food with a wide variety of nutritional content, including protein, via aquaculture.

In order to be sustainable, the feed-based protein must be vegetation-based. And since the building block of protein is nitrogen, we are looking for an adequate nitrogen source. Unused, wasted electricity can be used to make ammonia, which is a nitrogen fertilizer and, like a battery, can be used to store energy.

What does the future

look like?

Other than stable electricity, which would help us, our serious

concern is the anti-GMO Bill 79. It seeks to ban any new biotech solutions to farmers’ problems on the Big Island. The result is that the rest of the counties and the nation would be able to use new tools for more successful farming, and the Big Island would not.

What would happen is that Big Island farmers would become

less competitive, which would put even more pressure on those already at the bottom of the pay scale. It would result in higher food costs, making consumers less able to support local farmers.

The folks pushing for the anti-GMO bill have not talked to farmers, and they have no clue that this bill would make Hawai‘i less food

secure. The bottom line is that food security involves farmers farming. If the farmers make money, the farmers will farm. If not, they will quit.

The Wheres & Whyfors of Hamakua Springs

By Leslie Lang

The other day Richard gave some of us a tour of Hamakua Springs Country Farms in Pepe‘ekeo, and its new hydroelectric plant, and wow. I hadn’t been out to the farm for awhile, and it was so interesting to ride around the 600 acres with Richard and see all that’s going on there these days.

Most of what I realized (again) that afternoon fell into two

broad categories: That Richard really is a master of seeing the big picture, and that everything he does is related to that big picture.

Hamakua Springs, which started out growing bananas and then expanded into growing the deliciously sweet hydroponic tomatoes we all know the farm for, has other crops as well.

As we drove, we saw a lot of the water that passes through his farm. There are three streams and three springs. It’s an enormous amount of water, and it’s because of all this water that he was able to develop his brand new hydroelectric system, where they are getting ready to throw the switch.

The water wasn’t running through there the day we were there because they’d had to temporarily “turn it off” – divert the water – in order to fix something, but we could see how the water from an old plantation flume now runs through the headworks and through a pipe and into the turbine, which is housed in a blue shipping container.

This is where the electricity is generated, and I was interested to see a lone electric pole standing there next to the system. End of the line! Or start of the line, really, as that’s where the electricity from the turbine is carried to. And from there, it works its way across the electric lines stretched between new poles reaching across the land.

He asked the children who were along with us for their ideas

about how to landscape around the hydroelectric area, and also where the water leaves the turbine to run out and rejoin the stream.

“We could do anything here,” he said, asking for thoughts, and

we all came up with numerous ideas, some fanciful. Trees and grass? A taro lo‘i? Maybe a picnic area, or a water flume ride or a demonstration garden or fishponds?

There are interesting plans for once the hydro system is operating, including a certified kitchen where local area producers can bring their products and create value-added goods.

Other plans include having some sort of demo of sustainable

farming, and perhaps ag-tourism ativities like walking trails going through the farm, and maybe even a B&B. “The basis of all tourism,” he said, “is sustainability.”

Hamakua Springs is also experimenting with growing mushrooms

now, and looking into several other possibilities for using its free

electricity.

As we stopped and looked at the streams we kept coming

across, which ran under the old plantation roads we drove upon, Richard made an observation that I found interesting. In the Hawaiian way, the land is thought of as following the streams down from mountain to sea. In traditional ways, paths generally ran up-and-down the hill, following the shape of the ahupua‘a.

“But look at the plantation roads,” he said, and he pointed

out how they run across the land, from stream to stream. The plantation way was the opposite. Not “wrong” – just different.

Richard has plans to plant bamboo on the south sides of the

streams, which will keep the water cool and keep out invasive species.

At the farm, they continue to experiment with raising

tilapia, which are in four blue pools next to the reservoir.

The pools are at different heights because they are using gravity to flow the water from one pool to the next, rather than a pump. Besides it being free, this oxygenates the water as it falls into the next pool. They are not raising the fish commercially at present, but give them to their workers.

Everything that Richard does is geared toward achieving the same goal, and that is to keep his farm economically viable and sustainable.

If farmers make money, farmers will farm.

Continuing to farm means continuing to provide food for the local community, employing people locally and making it possible for local people to stay in Hawai‘i: This as opposed to people having to leave the islands, or their children having to leave the islands, in order to make a decent life for themselves.

The hydroelectric system means saving thousands per month in

electric bills, and being able to expand into other products and activities. It means the farm stays in business and provides for the surrounding community. It means people have jobs.

This is the same reason why, on a bigger scale, Richard is working to bring more geothermal into the mix on the Big Island: to decrease the stranglehold that high electricity costs have over us, so the rubbah slippah folk have breathing room, so that we all have more disposable income – which will, in turn, drive our local economy and make our islands more competitive with the rest of the world, and our standard of living higher, comparably.

When he says “rubbah slippah folk,” Richard told me, he’s always thinking first about the farm’s workers.

This, by the way, is really a great overview of how Richard describes the “big picture.” It’s a TEDx talk he did awhile back (17 minutes). Really worth a look.

It was so interesting to see firsthand what is going on at the farm right now, and hear about the plans and the wheres and whyfors. Thank you, Richard, for a really interesting and insightful afternoon.

What Is That Circle Around Us?

Richard Ha writes:

A bunch of things are happening right now. They look very different, but see if you notice what they all have in common.

We are just seeing the tomatoes start to produce more in spite of the dark, wet weather. It’s the third week of February; and last year, too, our tomatoes’ rate of production started climbing in the third week of February. That gives me a good feeling, because I’d been looking around and anticipating this.

All around I see growth. Avocado trees everywhere are choke with flowers right now. The ‘ulu are starting to develop on the tree; the ones I’m watching are about baseball size right now. Everything’s growing and producing around us.

We spent Saturday in Kona at a get-together for Armstrong Produce and its farmers. We stayed there for several hours, talking story with everybody.

I was sitting next to Timothy Choo, a chef from Sodexho, which does food service for UH Hilo. Sodexho is a huge supporter of local products, they go out of their way to buy locally, and we had a big conversation about it. Sodexho is supplied by Suisan, also a big supporter of local products.

I was also talking to Troy Keolanui, manager of OK Farms. Ed Olson owns that farm, 200 acres of many kinds of fruit and other trees, and we help distribute their produce under our Hilo Coast brand.

They are located behind Rainbow Falls, and they have a tent, with chairs in it, where they can sit and look at the falls. They purposely set it up behind some bushes so it doesn’t disrupt the more common view of Rainbow Falls, the one that tourists look at every day.

Then we drove back to this side of the island and went straight

to Puna. Chef Alan Wong was there, and he was throwing a small dinner for the farmers he buys from here.

Alan Wong and I started talking about the Adopt-A-Class project. I

said, “Why don’t we do a broader Adopt-A-Class project this time, in Puna. We’ll take the whole district and go to each of the schools there, including the charter schools. Everywhere there are elementary school kids.”

He’s into it. When we did this in the past, Alan Wong gave a class at Keaukaha Elementary School where he showed the kids how

to use tomatoes, and passed tomatoes around and had some of those kids eating, and loving, tomatoes.

Then yesterday, the folks from Zippy’s came by the farm. They’re going to open up a restaurant at Prince Kuhio Plaza soon and we’ll be supplying some of their products. Zippy’s has a strong “support local” program. When you go into any Zippy’s restaurant, you always see signs about which farms they get some of their products from. Zippy’s also uses local beef. It’s a corporate decision to support local growers.

Do you see the common link among all these things? Everybody’s coming at it from a different point-of-view, but the common

denominator is that we are so lucky to live here in Hawai‘i!

It’s all about local food and making ourselves food-secure. Our tomatoes are thriving and plentiful; where else in the country can you grow tomatoes throughout the winter? Other food is growing all around us.

Armstrong Produce distributes the products of many local farmers and producers. So does Suisan. Sodexo buy that local food.

And Alan Wong, too, is very interested in supporting local farmers and teaching local school kids. He’s very aware of the movement to be self-sustaining and is always reaching out to teach kids about where they come from, how their parents used to live and how we can live now. He’s all about helping people be grounded, and he comes at it with the training of a very high-level chef.

People are really helping each other out. Everybody has to make money, but they’re looking after the next person in the chain. If you’re the farmer, you’re hoping that your wholesaler is caring about you and not just the retailers. Everybody is look after everybody else.

It’s the only way I can figure out that we can help our own workers. Because, of everyone, who’s going to protect the workers? I’ve got to do everything I can to protect them.

There’s a big circle of sustainability around us, and it’s one that’s getting bigger and bigger. It’s really incredible, though it’s easy to get caught up in our busy lives and forget to notice.

Dispatch from the Philippines: We Can Learn a Lot from This Place

We left Cebu yesterday via Supercat (that’s a high-speed catamaran). Crossed the water and traveled along the east side of Leyte Island.

The island is like Hawai‘i, with highlands in the middle. It seemed like there were cinder cones all over its surface. Due to its lack of erosion, Leyte looks relatively younger geologically than O‘ahu.

There was a huge welcoming ceremony. Beauty queens, band, dancers, dignitaries and a police escort. Each of us received an Ormoc City medallion to wear around our necks. Serious stuff.

After dropping off our bags, we went to Visayas State University (VSU). Our delegation met with the President of the University and had a briefing, where it was apparent that there are so many things we have in common. I loved the atmosphere and “can-do” attitude.

Big Island Mayor Billy Kenoi set the big picture – the Aloha connection. This relationship is a long-term one of friendship.

Dr. Bruce Matthews, Interim Dean of the UH Hilo College of Ag, delivered UH Hilo Chancellor Donald Straney’s message of wanting to set up a student exchange program, and they are trying to achieve a Memo of Understanding on that before we leave. Their “cut through the red tape” attitude was most impressive to me.

VSU is a high-tech learning and research center that is building on what works locally, and then improving on it. For example, carabao – water buffalo – are utilized throughout the islands. But the university is improving the native carabao line by bringing in stock that grows faster in relation to a given time and food supply.

Also, carabao milk is thick, and not as appetizing as cow milk, but by diluting it by 50 percent with water, you end up with the nutrition equivalent of cow’s milk. Hmmm! We sampled carabao yogurt and it was wonderful. And it grows best on Hilo grass. Hilo grass? That is what survives overgrazing and mowing on the Big Island. And it goes on and on.

Third World? We can learn a lot about sustainability from this place. Mayor Billy sets the right tone for a long lasting and mutually beneficial partnership.

Sustainability in Hamakua

My worlds collided on Saturday, when I led a tour that included a stop to meet Richard and see Hamakua Springs Country Farms.

Along with Hilo historian and anthropologist Judith Kirkendall, I lead van tours around East Hawai‘i. Right now we are doing a series of five tours that focus on agriculture and sustainability – what people are doing right now to be more sustainable, and how we can support them and also be more sustainable ourselves. The tours operate through Lyman Museum.

Our tour this past Saturday was called “The Garden As Provider,” and we focused on Hamakua. First we met at the Lyman Museum and heard a short talk by Sam Robinson about Let’s Grow Hilo. That’s the program she started that has volunteers planting edibles along downtown Hilo streets and in traffic medians.

“Anyone is free to help themselves to the fruit or vegetables once it’s ripe,” she told us, and she invited anyone interested in the project to come help plant and tend. They meet every last Sunday at the East Hawai‘i Cultural Center at 2 p.m.

Then we visited Barbara and Philip Williams, who live just outside Hilo near Pueopaku. Barbara grew up in Kenya, where they lived 50 miles away from the nearest railroad and so had to be self-sufficient. After she and Philip married, they lived on a plantation in East Africa. Now on the Big Island, they still grow and harvest everything they can. They have animals, including goats, and every fruit and vegetable you can imagine. “We retain the habits of being self-sufficient to the present day,” she told us.

From there we headed to Pepe‘ekeo, where Richard met us at Hamakua Springs.

Richard is such an interesting speaker. He told us the story of how he started in farming (after flunking out of UH and consequently serving in Vietnam, he returned home and helped his father on the family’s chicken farm; then traded chicken manure for banana keiki and started farming bananas). He talked about how they decided to move the farm to Pepe‘ekeo and why (hint: free water; the farm alone has one-third as much water as supports agriculture where 234,000 people live in Leeward O‘ahu). Our tour group was totally engaged.

He told about how he started noticing prices going up (on fertilizer, boxes, all the things they were using on the farm) and how he realized it was due to oil prices and decided to attend Peak Oil conferences to learn what was happening. And how he felt bad and so didn’t tell the others there that he would return to Hawai‘i and wear shorts throughout the winter, and grow his produce throughout the winter; nor how we have geothermal to provide us with energy – which we don’t even fully take advantage of.

He spoke about how he has been positioning themselves for how conditions will be five or 10 years from now, and about the hydroelectric project that is getting going on the farm very shortly, and how since his workers first asked to borrow money for gas to get to work he has started what they call the Family of Farms, working with nearby farmers. And about how they are experimenting with how they can produce protein on the farm by raising tilapia, and giving their workers fish (and produce) every week in lieu of monetary raises they cannot afford to give right now.

There was more, and as editor of this blog for all these years, none of it was new to me, but I, too, listened intently and enjoyed it thoroughly. It was fascinating to hear Richard pull all the pieces he talks about on this blog together into one, interrelated, narrative that tells such a real, on-the-ground story of how things are (and how they are changing). The people on the tour were really interested. We all were. Afterward, I heard people talking about what a great thinker he is, and how much they enjoyed meeting him.

That Richard, he’s all right!

We also went to Hi‘ilani Eco House in Honoka‘a, an amazing house being constructed to be as “green” as it gets. Wow, that’s a fascinating place (they say it should last for 500 years!) and they are very open to groups visiting, if anyone is interested. And we stopped a couple other places as well.

It was a neat day (the upcoming tours are listed here if you’re interested), and Richard’s information really made it so good. We were all wowed. Thanks, Richard!

Scientists With Heart & Common Sense

The scientists at Pacific Basin Agriculture Research Center (PBARC) in Hilo are pursuing their project of “zero waste.” The objective is to utilize all the byproducts of agriculture production in a sensible way.

Their funding had been cut to the bone. But Director Dennis Gonsalves and the scientists there are refusing to give up. They are doing it because they believe in sustainability for Hawai‘i.

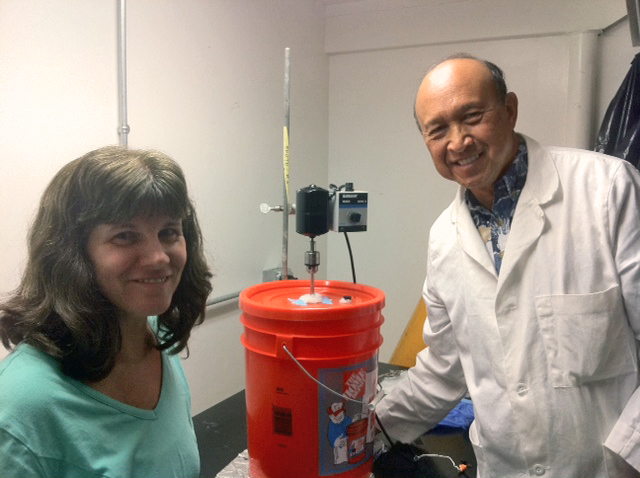

This is Marissa Walls, research food technologist at PBARC, and Dennis Gonsalves.

I wrote previously about their algae-to-oil for waste papaya. They started with a test tube of a specially evolved algae that preferred papaya as its food, and it produced oil.

They started the papaya algae-to-oil trial at a 1-liter scale.

This is a short video clip of the algae on a shaker.

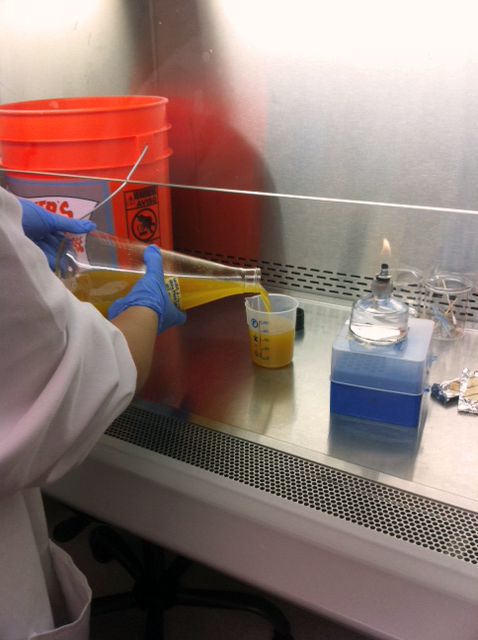

Now they are scaling up the process to a 5-gallon size. I was there to witness the first batch being done. First they took the papaya mixture into a special hood, where filtered air was brought in causing positive air flow out of the front. This prevented unfiltered air to come in from the outside.

Just before taking the 5-gallon bucket to the next room, they took a sample of the mixture to test for contamination. If mixture is contaminated by something that grows faster than the algae, they’ll know.

Here is Dr. Gonsalves transferring the first of the 5-gallon batch. Note that the bucket is a plain plastic bucket. They got it from Home Depot.

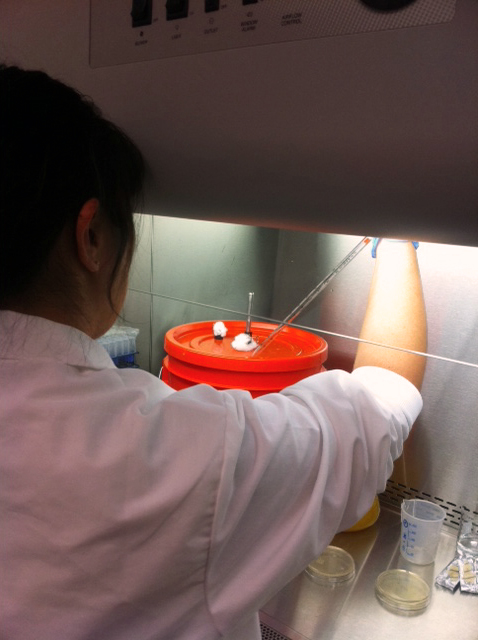

Because they don’t have funding for a lab, they are using a space under the stairwell of the PBARC building. The algae functions in the dark, so they have black plastic taped to the stairwell to maintain the dark.

There the mixture will be constantly stirred. Instead of a shaker, the 5-gallon bucket mixture is agitated by what looks like a paint mixer.

Dr. Gonsalves tells me that they are getting batches of new evolved algae as they go along, and after a bunch of tweaking by these smart scientists, they have got the oil yield up to 35 percent. After the 5-gallon scale, they will go to 50-gallon and then to 1000 gallons. The mixing, sterilizing and dewatering procedures will change as appropriate for each scale.

I can very easily relate to that. It’s exactly what we did when we scaled up our farm from one acre to 600 acres. These are common sense scientists. I could not be more impressed.

One of the scientists is now looking into the nutritional content of the leftover algae cake. I can’t wait to see if it can be used for fish food. Just imagine, farm waste to oil and then the leftover for fish food. Sounds like common sense to me.

Dr. Gonsalves’ objective is to have real numbers and actual oil for evaluation within a year.

This project is impressive because it focuses on value to society as its end result. Many times, money as an end result goal takes us in a direction we don’t want to go. This project’s focus, and its methods, are simple and practical.

We farmers characterize it as common sense. Nowadays, that is high praise.