The Ku‘oko‘a Board of Directors recently briefed a group of influential people on what we are all about.

Former CIA Director Jim Woolsey talked about our dependency on oil, and its national security implications. He talked about Hawai‘i’s situation – that we have the potential to free ourselves from the tyranny of oil – and explained that this possibility is what made him want to be involved.

Former U.S. Department of Energy Deputy Secretary TJ Glauthier, who brings a high level of experience to our team, spoke about the Ku‘oko‘a business plan, and said that the preliminary numbers do work.

Former Harvard Professor of Entrepreneurship, and current UH Shidler College of Professor, Rob Robinson acted as moderator. He explained why the Ku‘oko‘a model, which emphasizes a low cost of electricity, is so important to the future of Hawai‘i.

Venture Capitalist Roald Marth, who is also CEO of Ku‘oko‘a, spoke about how he came to be involved in the energy issue, and how he has committed his life to freeing Hawai‘i from fossil fuel. Ro has been relentless in his efforts.

Former Hawai‘i State Energy Administrator Ted Peck walked everyone through the basic Ku‘oko‘a plan.

It’s a powerful team. At the end, there was a Q&A period, during which board members answered questions and addressed comments from the audience.

I spoke first, and here is what I said:

Aloha Everyone,

I am Richard Ha, Chairman of the Board of Ku‘oko‘a. Ku‘oko‘a is trying to align the needs of the people with the needs of the utility.

I am a farmer, so I tend to go straight to the essential elements. The world has been using three times the oil it has been finding for the last 30 years. In 2003, oil price was between 20 and 30 per barrel. The price rose steadily, yet the supply did not increase. Sooner or later we will start to drop down the backside of the oil supply curve.

In addition, because it is taking more energy to get energy, the net energy left over to do work will also decline. And on top of this, China and India’s people cannot wait to jump in their cars to drive to McDonalds. And the oil exporting nations have to use more oil for their own people, or they will get thrown out of office.

All these things occurring simultaneously tell us that the safety of the status quo, where Hawai‘i relies on oil for 76 percent of its electricity generation, is increasingly not safe.

Since we are talking story here, I want to tell you who I am and what my values are. Mom is Okinawan, Higa from Molokai. Pop’s father was Korean – Ha, and his mom was Leihulu Kamahele. Her mom was Meleana Kamoe Kamahele and her dad was Frank Kamahele. Our family land was down the beach at Maku‘u, in Puna.

We were very poor, but we didn’t know it. Pop would tell stories at the dinner table where he would talk about impossible situations, impossible odds.

Then he would pound the table and point in the air. “Not, no can. CAN!”

And he would say, “There are a thousand reasons why no can. I only looking for the one reason why can.” He told us to find three solutions for every problem, and then find one more just in case. He finished 6th grade but he was a wise man.

I was a kolohe kid growing up. I went to UH Manoa, where I flunked out. Too many places to go, people to see and beers to drink. I was drafted and applied to go to Officers’ Candidate School, and then I volunteered to go to Vietnam. Ended up walking in the jungle with 100 other soldiers. If we got into trouble there was no one close enough to help us. The unwritten rule was that we all come back or no one comes back. I liked that and have kept that attitude ever since.

I went back to UH and majored in accounting so I could keep score when I went into business. Pop asked if I would come back and help to run the family chicken farm. I came back and saw an opportunity to grow bananas but I had no money.

“Not, no can. CAN!” So we traded chicken manure for banana keiki. By questioning everything, looking into the future and forcing change, we were able to survive in farming for more than 30 years. We farm 600 fee simple acres outside of Hilo with 60 workers. It just goes to show that anything is possible.

We are not afraid to try stuff. I was given the University of Hawai‘i College of Business’s “Hall of Honor” award, as well the UH’s Distinguished Graduate award, for my role in bringing theThirty Meter Telescope to the Big Island. That is a $1.3 billion project, and it was a foregone conclusion that it was going to Chile until we went to work engaging our Big Island community here. It’s now coming to the point in the legal process where construction can begin in a short time.

Our family’s company was the first banana company in the world to be certified ECO-OK by the Rainforest Alliance, the largest third party certifying organization. That was reported widely in the banana producing areas of Central and South America. In fact, they scrambled to find a farm in Costa Rica who could be certified along with us, so we both could say we were first in the world. And it had a big influence in changing the environmental behavior of the Doles, Chiquitas and Del Montes.

We were one of six national finalists for the SARE award, a sustainable production award open to all farms in the nation. I mention all these things because we live by the spirit, “Not, no can. CAN!”

One day five years ago, we realized that our farming supply costs had been steadily rising, and found that it was all due to oil. So I went to go learn about oil so we could reposition our company for the future. I was the only person from Hawai‘i to attend three Association for the Study of Peak Oil conferences.

The main lesson there was that the world had been using two to three times the oil it had been finding for the last 30 years, and that soon, the game will be up.

Coming back to Hawai‘i, we repositioned our farm and soon we start construction of a hydroelectric plant that will take us completely off the grid.

Several years went by, and then I met Ro Marth and we embarked on this project. It made total sense to me. First it was Ro, myself and Ted Peck. The paper called us the government bureaucrat, the tomato farmer and the motivational speaker. It was kind of humorous.

We did not let ourselves get distracted, but went about doing our work – first by putting our board together. We needed to be credible with Wall Street, Bishop Street and Kinoole Street. Especially Kinoole Street. This needed to be a company that the rubbah slippah folks would see as local, and, preferably, their own.

It’s all about people, and we have put together a strong team. We have incredibly smart, caring and courageous people. Our diversity is what gives us our strength, and also we watch each other’s backs. And we would love for courageous folks, who can see a brighter future for Hawai‘i, to join us.

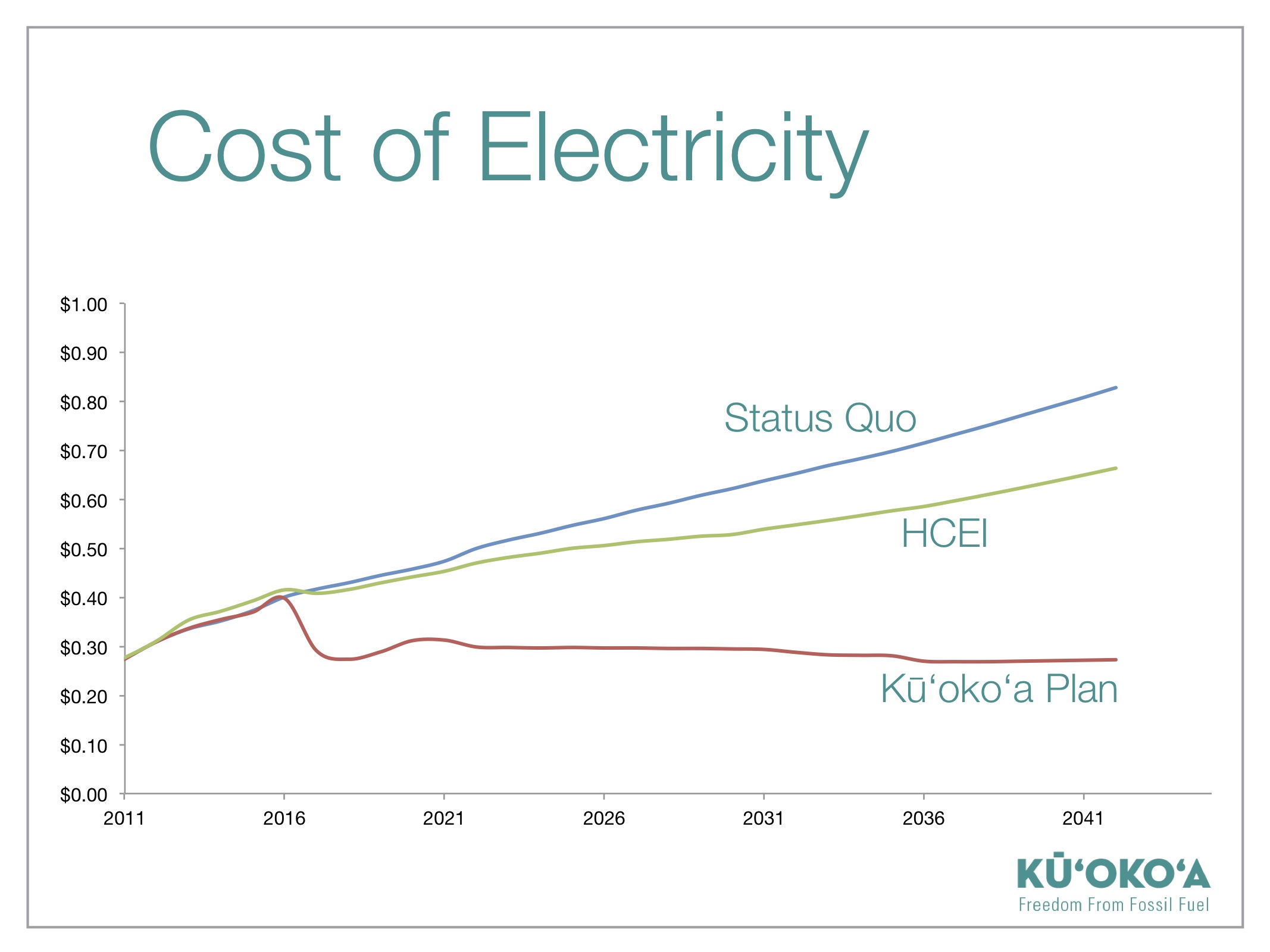

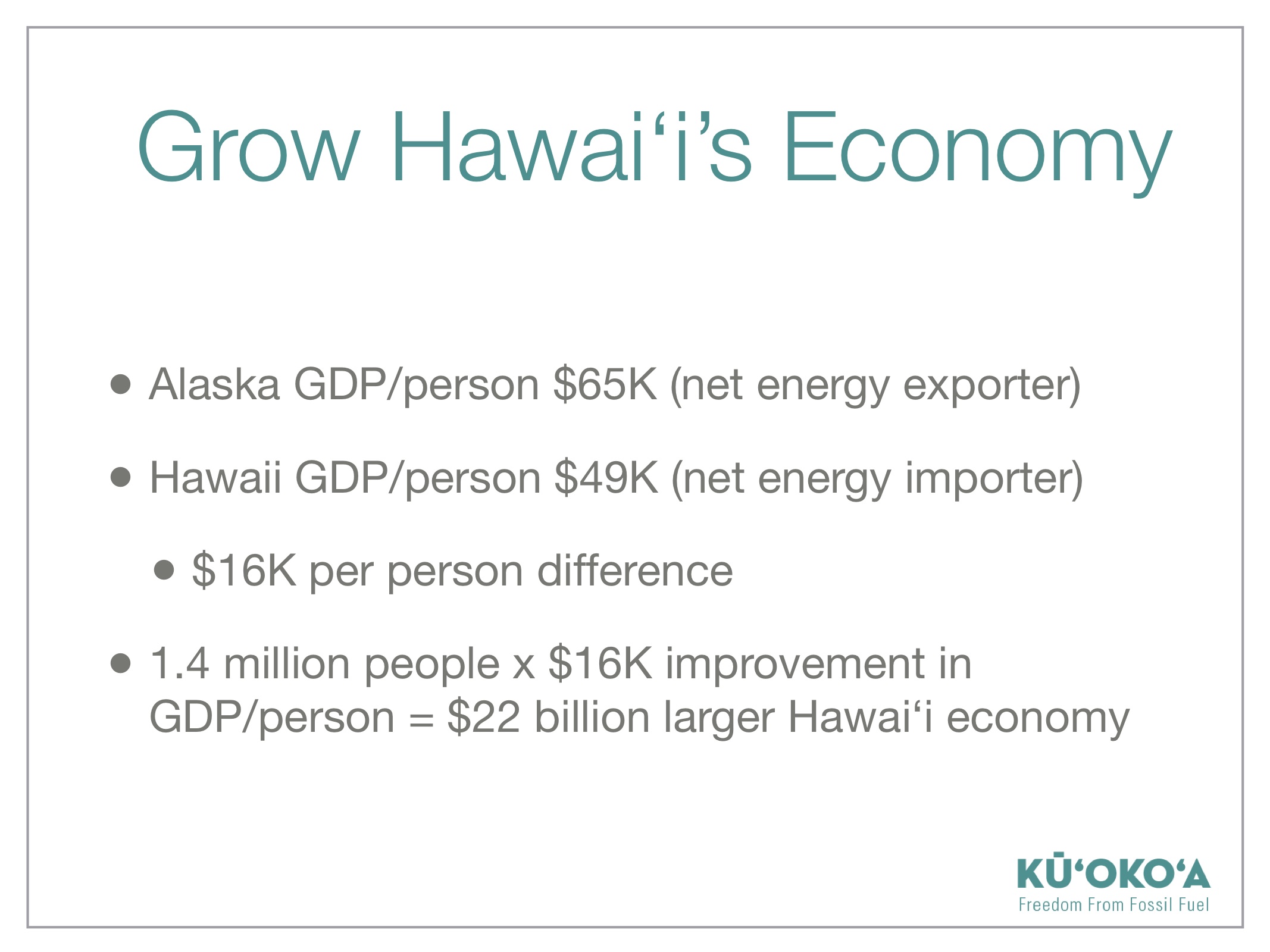

Ro and I visited Iceland recently. Iceland has managed to make itself energy secure and food secure by using cheap geothermal and hydro. Its electricity costs are less than half of ours. In Iceland, they export energy in the form of aluminum, and that allows them to buy food. The cheap-energy sector of their economy is helping the country recover from its banking sectors meltdown. Low cost energy makes them competitive with the rest of the world. Not high cost energy.

Mayor Kenoi will soon sign a sister city document with the Mayor of Ormoc City in the Phillipines. They have the same population as the Big Island, but Ormoc City produces 700 MW of electricity with its geothermal, compared to our 30MW.

We are very fortunate to have geothermal on the Big Island. It costs less than 10 cents/kWh to generate electricity from geothermal, while it costs more than 20 cents/kWh to generate electricity from oil.

Can we find the solution to our energy problems while taking care of the rubbah slippah folks too? It’s about the cost of energy. If we choose an expensive alternative for electricity, we know that folks on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder will get their lights turned off first. Leaving the rubbah slippah folks behind should not be an option. If we try hard enough to find solutions, we should be able to take care of everyone.

One of our solutions is to replace oil with geothermal as base load for the generation of electricity. One day, I asked Jim Kauahikaua, Chief Scientist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, “Eh Jim, how long the Big Island will be over the hot spot?” He said, “Between 500,000 and a million years.” I thought to myself, “That should be long enough.”

In modern Hawaiian history, the economy has taken taken taken and the culture has given, given, given. We have a unique opportunity now where the economy can give and the culture can receive. If we can stabilize energy costs at a low level, we will become more competitive to the rest of the world as oil prices rise and our people’s standard of living will rise. We can address the energy problem and take care of the rubbah slippah folks too.

We can look forward to handing our children and their children’s children a brighter tomorrow.

We are looking for like-minded, brave folks to join us and help bring about the kinds of change that will take all of us into a brighter future.

As my Pop used to say: “Not, no can. CAN!”