A couple days ago I got a note from Henry Curtis saying he was on the Big Island for a few days of rest and relaxation, and that he wanted to drop by and talk story. Henry is executive director of the environmental group Life of the Land.

Since I had planned to plant bamboo, I figured we could talk story and do that at the same time. So I picked up Henry and his partner Kat Brady and took them riding in one of our Woods 4x4s.

As we drove, I pointed out the three ahupua‘a that run through our farm and the characteristics of each. Then we drove to the top of the ridge line that is the prominent feature of Kahua ahupua’a. From there we could see most of the farm and I pointed out the main features of each hupua’a. We could see the streams by the trees that grow alongside. I explained that I am interested in reclaiming the stream banks from invasive trees and grasses.

We talked about food security, energy security and community and after awhile we talked in shorthand because it was apparent that we all understood what is happening with oil and the direction the world is moving in. They absolutely understand farming —that it is not easy or automatic. I was happy to know that about them.

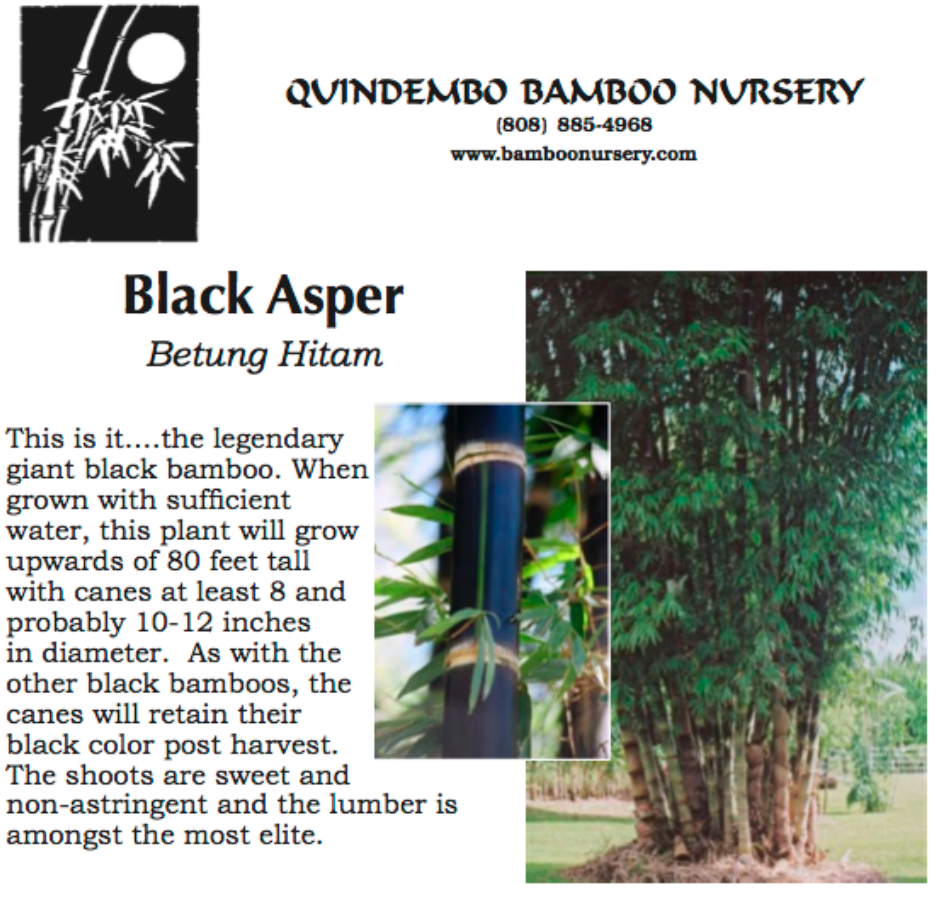

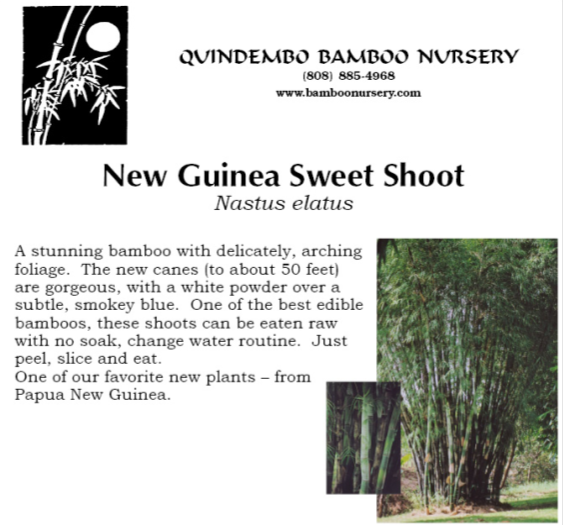

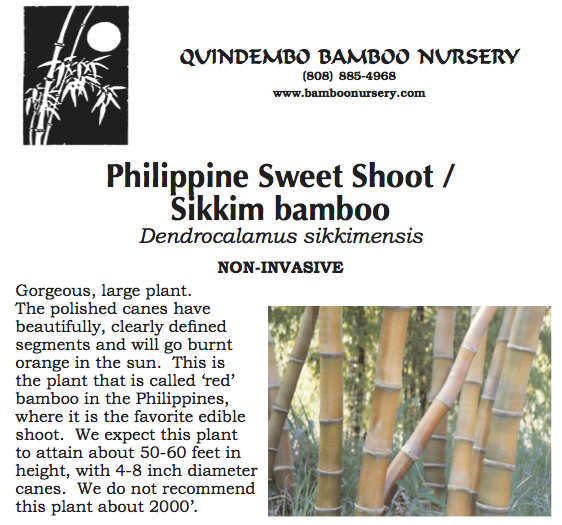

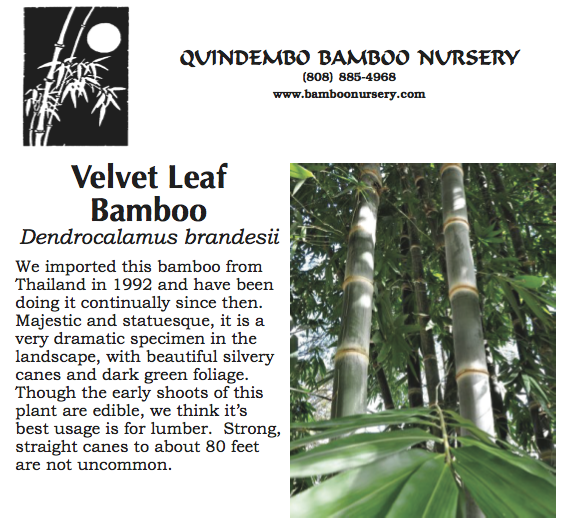

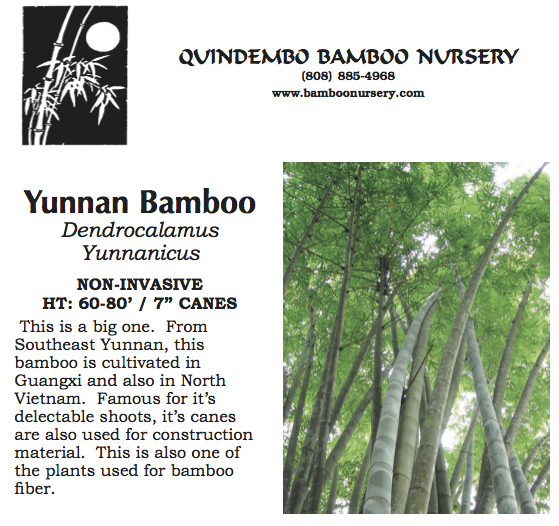

On the old sugar plantation field maps, sugar cane field acreages were written on the maps. The sugar companies raised sugar cane right to the riverbanks, so they used most of the land. But since then, invasive trees have started growing on the stream banks and now they are everywhere and moving into productive agricultural lands. We want to reclaim the productive land and plant bamboo in the non-productive land. In that way, we will maximize the productivity of our land area.

I told Henry and Kat that I want to use bamboo as a way to reclaim the streams and put the non-productive stream banks into production. When they are in season, June wants to give bamboo shoots to our workers. The bamboo provides a primary windbreak for our bananas, and planted on the south side of streams, its shadow falls on the water, keeps it cool and helps to suppress pest trees. Bamboo can even be used for the construction industry.

Jerry Konanui had asked for photos of the kalo plants I recently found in Makea stream. So I asked Henry folks to help me get some plants. Here are a couple of them. In a couple of hours they were all wilted, so I gave them to Grandma to replant in the nursery. We want to make sure we do not lose the species. When they’re stronger, we’ll give them to Jerry for identification.

Next we went up to the site of our hydroelectric project. I pointed out how lucky we were to have this great amount of water constantly flowing. On our property alone we have about 1/3 of the total amount of water that comes across the Waiahole Ditch on the way to Central Honolulu. Once I counted 35 streams between Hilo and Honoka‘a.

We had a very fun visit. Kat told me she loved the smell of dirt on her hands.