Richard Ha writes:

Christine Lagarde, director of the International Monetary Fund, just gave a very significant speech about where the world is at right now, and—very interesting—how similar it is to where the world was at exactly one hundred years ago, in 1914.

I was struck by how, right now, right here in Hawai‘i, we are a microcosm of what was happening in the world a hundred years ago.

From Christine Lagarde’s speech:

I invite you to cast your minds back to the early months of 1914, exactly a century ago. Much of the world had enjoyed long years of peace, and giant leaps in scientific and technological innovation had led to path-breaking advances in living standards and communications. There were few barriers to trade, travel, or the movement of capital. The future was full of potential.

Yet, 1914 was the gateway to thirty years of disaster—marked by two world wars and the Great Depression. It was the year when everything started to go wrong. What happened?

What happened was that the birth of the modern industrial society brought about massive dislocation. The world was rife with tension—rivalry between nations, upsetting the traditional balance of power, and inequality between the haves and have-nots, whether in the form of colonialism or the sunken prospects of the uneducated working classes.

By 1914, these imbalances had toppled over into outright conflict. In the years to follow, nationalist and ideological thinking led to an unprecedented denigration of human dignity. Technology, instead of uplifting the human spirit, was deployed for destruction and terror. Early attempts at international cooperation, such as the League of Nations, fell flat. By the end of the Second World War, large parts of the world lay in ruins.

Right now, in 2014, we are heading into difficult times, which in fact have already started. We already see how the skyrocketing price of oil has impacted all our costs. Everything is, noticeably, much more expensive: electricity, plane tickets, gasoline, retail goods that have to be transported here, food that needs fertilizer and has to be cooled enroute here. Everything—and it’s only going up.

The story of 1914 is the story of what’s happening in Hawai‘i right now. We have serious divisions, and people yelling at each other about important issues. I don’t see people trying to come together to solve the many problems we are facing. Are we going to go the same way?

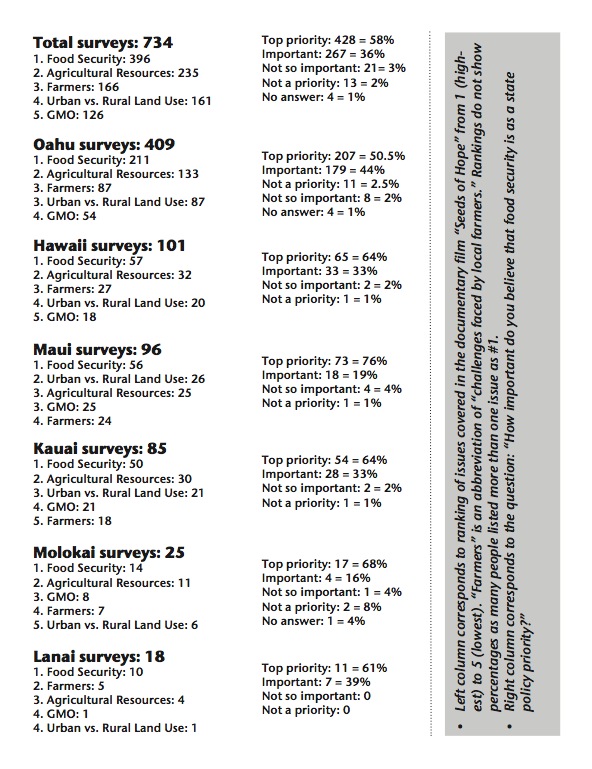

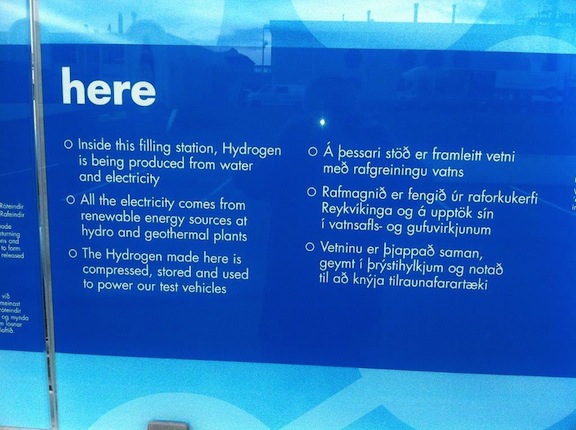

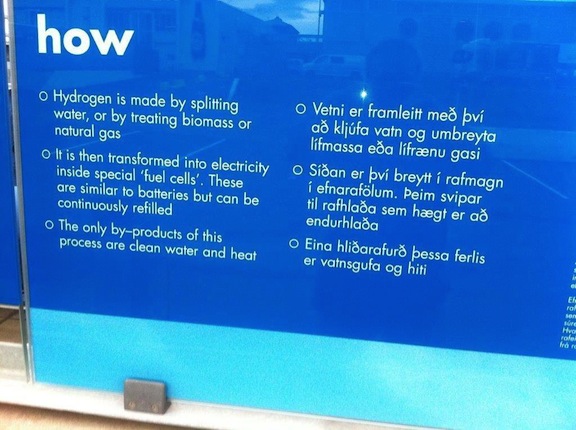

They’re doing it right in Iceland. A few years ago, Iceland had the biggest financial meltdown in history, and they’ve turned it around very successfully. They looked at their resources, and used them very well. It’s working.

We are not doing this. Right now, everyone is running around trying to force solutions that benefit themselves. But individual solutions aren’t going to work. We need a big picture solution. We have to come together to seek answers for all of us.

As in Iceland, what we have going for us here is our geothermal potential. I’ve said this so many times now that it sounds like I have an agenda, but I don’t. I don’t gain anything from our increased use of geothermal energy except for what we all will gain: stable energy costs, stable food costs, stable everything costs. The ability to better afford living in Hawai‘i. The pleasure of knowing our kids and grandkids will be able to afford to stay and establish their career and family here, instead of taking off for a cheaper location on the mainland.

An increased use of our geothermal resource will make a big difference in the quality of our lifestyle.

Some people say solar energy is the answer, but that’s not it. Hawai‘i had the highest number of solar installations ever last year. Twenty years from now, when those people have to put on a new roof and redo the solar panels, what will the economy look like then? If oil spikes, they might not have the financing to pay for it. Will they be able to afford it?

The geothermal plant I toured in Iceland could last 60 years. My hydroelectric pipe will last 100 years. Solar is a temporary answer, and maybe it’s a bridge, but it’s not the solution.

Back to Lagarde: What happened to end those 30 years of war and economic disaster was that in 1944, leading economists from around the world came together in New Hampshire.

In her speech, Christine Lagarde said:

The 44 nations gathering at Bretton Woods were determined to set a new course—based on mutual trust and cooperation, on the principle that peace and prosperity flow from the font of cooperation, on the belief that the broad global interest trumps narrow self-interest.

This was the original multilateral moment—70 years ago. It gave birth to the United Nations, the World Bank, and the IMF—the institution that I am proud to lead.

The world we inherited was forged by these visionary gentlemen—Lord Keynes and his generation. They raised the phoenix of peace and prosperity from the ashes of anguish and antagonism. We owe them a huge debt of gratitude.

Because of their work, we have seen unprecedented economic and financial stability over the past seven decades. We have seen diseases eradicated, conflict diminished, child mortality reduced, life expectancy increased, and hundreds of millions lifted out of poverty.

Now, in 2014, which direction are we going to take? The path they went down in 1914, which led to crisis and disaster? Or the 1944 coming together, which changed the disastrous path they/we were on, and from which we are still benefitting?

Let’s not go through 30 or more years of crisis and disaster. Let’s learn from the past, and from what others are doing around us. Let’s all pull together and think on a bigger scale.

Lagarde’s speech was titled, “A New Multilateralism for the 21st Century: the Richard Dimbleby Lecture.” You can read it here. Or watch the video here.