Category Archives: History

Kamahele Family, Part 5 – What Uncle Sonny Kamahele Taught Me

Let me tell you something really interesting I learned from my Uncle Sonny Kamahele. He had 20 acres in Maku‘u, in Puna on the Big Island. There was a rare kipuka there with soil that was 10 feet deep, no rocks or anything. There was a spring in one corner of his property.

I was just out of college with an accounting degree and lots of ideas about business. So I looked at his land and wondered if he would lease me 10 acres to grow bananas. I scratched my chin and thought about how I could grow 35,000 pounds per acre on those 10 acres. Maybe 300,000 pounds a year if I took into account turn around space.

And yet on the other 10 acres, Uncle Sonny was making his living with just 10 or 20 hills of watermelons, with maybe four plants on each hill. People would come from miles around to buy his watermelons. It provided him with enough income to support himself and to send money to his wife and son in the Philippines.

Here’s the lesson I learned from him: It’s not about how big your farm is. Your business is successful if it supports your situation. I learned a lot from Uncle Sonny, but I think that’s the most important thing I learned from him.

That’s what I always look at when I visit a farm. Not how big it is, or how much money it makes, but how it operates, and whether it solves the problem it is trying to solve.

Here’s why I’m telling you this right now. We have a real energy problem looming. I think the situation with oil is very serious, and there are definitely going to be winners and losers in the world. We need to position ourselves to be winners, and it’s going to take all of us, big and small.

How are we going to feed Hawai‘i?

Every one of us is going to play a role in it – from the largest farmers to the small folks growing food in their backyard. Do you remember in the plantation camps, especially the Filipino camps, how the yards were always planted with food? Beans, eggplants, the whole thing. I don’t see it so much anymore, but we can do it again.

We are lucky on the Big Island. We’re not crowded and everybody has room to grow food. You know how you can tell we have plenty space? Everybody’s yard is too big to mow! We have the ability to do this.

It’s going to take all of us. It’s not just about any one of us, it’s about all of us, from the biggest to the smallest.

I’m lucky to have had my Uncle Sonny Kamahele to learn from when I was younger. I spent a lot of time with him and I got a real feeling for how he made decisions, which was old style.

Uncle Sonny Kamahele and lifestyle

His lifestyle was a real connection to the past, too. He kept his lawn and the whole area immaculate, practically manicured. He lived pretty close to the old ways with a lot of remnants from the past. His red and green house had stones from down the beach under the pillars, and lumber over the dirt floors. He built beds on those floors and then had five or six lauhala mats on the beds instead of mattresses; old style. There was a redwood water tank.

He listened to the County extension folks, and I learned from that, too – to pay attention to the people who know something.

But one of the most important things I learned was that your business, big or small, is a success if it supports your particular situation.

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

Maku‘u Stories, Part 3: Uncle Sonny Kamahele

Maku’u Stories, Part 4: Tutu Meleana & the Puhi

Kamahele Family, Part 4 – Tutu Meleana & the Puhi

Reposting a story I wrote several years back:

I just received a really interesting email about my Tutu Meleana. It was from my cousin Danny Labasan, and I’m copying it here with his permission:

I am the last son of Elizabeth Kamahele. I’m not sure if we met but we could have. I was so young way back then, I can’t remember who all of my cousins are. But I do remember once we went over to the chicken farm. I don’t know if Kimana or Kuuna was your dad. They were in Makuu all the time.

But how this writing came about is that I am doing some Kamahele family tree background. And while doing some Internet checks I ran across your articles via Hamakua Springs.

I just want to say that the stories you write, especially about Tutu, Uncle Sonny, the Maku‘u land, are so so so soo great. It’s like I am still there.

I wrote back that I know of him, though I don’t remember if we met either. His mom was Aunty Elizabeth, and I told Danny I have fond memories of her. I told him my dad was Kimana, which was a Hawaiianization of Kee Mun Ha, the name my dad’s Korean dad gave him.

Danny told me this great story about Tutu Meleana, who lived there at Maku‘u. Though Danny and I are near in age, Tutu was Danny’s grandmother and my great-grandmother.

The pond that you spoke of (Waikulani) where Tutu took you, and us as well, to fish as little kids – I have a story to tell about it. I will never forget it because it’s why I hate puhi (eel).

On one particular day, Tutu and my mom Elizabeth went to this pond. We swam and fished. Aunty Elizabeth caught lots of ‘opihi and Tutu caught some haukeuke. Then Tutu showed us how to clean the fish, the ‘opihi and haukeuke. We were on the rocks just feet from the ocean water. I was probably 6 years old. This will be hard to believe but a puhi came flying out of the water and grabbed hold of Tutu’s bicep. I will never forget seeing this snake-like creature attached to Tutu’s arm. I screamed until I hyperventilated.

But Tutu was so calm. She grabbed hold of the puhi’s head, pushed it against her arm and the mouth of the puhi opened up, and Tutu was able to remove the puhi from her arm. She cut the head off. Patched up her arm and we walked back to the house. An experience I will never forget. I still hate puhi.

My brother Allen, he was called Eloy during those days, would take us fishing in Kukuihaele where we lived and he would show us how Uncle Sonny and cousin Kalapo would catch puhi. Unreal.

Waikulani

What a story. Waikulani Pond is not exactly a pond. It was a place where the large waves outside would break on a protective ring of pahoehoe, and small swells would roll gently across what looks like a pond. One would have to jump from rock to rock to get to Waikulani. The bigger kids could do this, no problem.

The small kids would all go poke around in this tiny, protected cove, looking at ocean animals, and would sometimes see the dreaded puhi.

Great story, Danny. Thanks again.

See also:

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

Maku‘u Stories, Part 3: Uncle Sonny Kamahele

Kamahele Family, Part 3 – Uncle Sonny Kamahele

My Uncle Sonny Kamahele farmed at Maku‘u after some years in the Merchant Marines. His real name was Ulrich Kamahele (I have no idea where that name came from). He had a big personality.

One day, when I was walking with a couple of my buddies on Waianuenue Avenue near where Cronies is now, I heard someone call me. It was Uncle Sonny, and he was almost all the way up the block toward Kaikodo.

It’s hard to be rugged — even when you are in the 9th grade and smoking cigarettes — when your Uncle Sonny yells “Eh, Dicky Boy.” I cringed and looked around to see if any girls had heard him. He must have been in his 30s then.

I caught up with him again after I graduated from the University of Hawai‘i and returned home to run Pop’s chicken farm. When we decided to start growing bananas, we got lots of our banana keiki from Uncle Sonny. The Paradise Park subdivision had been built and so one could drive all the way down to Maku‘u. So we saw him quite frequently.

Uncle Sonny did not have electricity, running water or a telephone, but he had a transistor radio and a 1-foot stack of U.S. News and World Reports. He always got the current copy from the Pahoa post office. Though he lived a very simple life, he’d traveled all over the world with the Merchant Marines and he knew a lot more than one would think. He could talk about a myriad of subjects. I found his stories fascinating.

I visited him often and learned a lot about farming from him. A visit to Maku‘u would take hours, with most of that time spent listening to Uncle Sonny. I learned to be a good listener. He always talked in a loud voice and he waved his arms a lot. My wife June and my sister Lei told me that they would stay arms’ length from Uncle Sonny, walking backwards or in a big circle around the yard. They were careful to stay out of range of his swinging arms, so they wouldn’t be all bruised at the end of the visit.

Everyone knew Uncle Sonny for growing the sweetest watermelons. People would come from miles around to get his watermelons. He did not have to go out to sell them; they would all sell by word-of-mouth.

We spent a lot of time talking about farming watermelons. He used a backpack poison pump. Once he showed me how he knew that the amount of sticker/spreader in the mixture was effective. Although the rate was supposed to be something like ½-teaspoon per gallon, he always double-checked the mixture by sticking a piece of California Grass into it. Due to the fine hair on the grass, water normally runs off California grass, taking the herbicide with it. If the water spread on the leaf instead of running off it, the mixture was right.

What I learned from Sonny Kamahele

The message I learned: Use the book for the first approximation, and then confirm things on the ground. The word “grounded” does come to mind.

He told me that melon flies, an enemy of watermelon, rest under a leaf at the height of the midday sun. That was why he planted a few corn plants on the outside border of his watermelon patch. Sure enough, they were there. He was in tune with the behavior of the fruit fly. He would pull out his can of Raid and give them a short burst.

The standard solution would have been to spray the whole field. Uncle Sonny’s way was much more effective and very much cheaper.

Here’s how Uncle Sonny knew his watermelons were ready: When they reached the size of golf balls, he put a wooden stake with the date on it. Then he harvested the melons after a certain number of days went by.

It was so simple and so effective. It’s what led us to place a different colored ribbon on every banana bunch we bagged in a particular week. We harvested the bananas based on elapsed time—pretty much like Uncle Sonny did.

I learned from Uncle Sonny to use the “book” for general instructions. But not to rely on it exclusively.

Uncle Sonny broke things down to their essential components. He made his life simple, and yet he was very effective. I admired him very much.

See also:

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Maku‘u Stories, Part 2: Frank Kamahele

KAMAHELE FAMILY, Part 2 – Frank Kamahele

I’ve been talking with my extended Kamahele family over on my Facebook page. We’ve also started a private Facebook group for Kamahele descendents, where we are discussing our genealogy and sharing memories. Let me know if you’re related and would like to join.

It’s all got me thinking about our Kamahele family of Maku‘u and how it was back then. On Mondays right now, I’m reposting five posts I wrote back in 2009 about life in Maku‘u and my family there. Here’s #2.

My cousin Frank Kamahele

It was because he stayed at Maku‘u when he was a small kid that my Pop’s cousin Frank Kamahele became a jet pilot and also the manager of the Hilo and Kona airports.

About a mile down the coast from Tutu’s house in Maku‘u, toward Hawaiian Beaches, was an island called Moku ‘Opihi. During World War II, Hell Fire and other planes flew from Hilo and used that island for target practice.

The pilots knew there was a small kid at the house who jumped up and down waving at the planes. Some would fly low and turn sideways, then smile and wave at the small kid. Others would wiggle their wings and buzz the house.

The small kid knew that he would become a pilot one day. He did not know how; just that he would.

Later, when that kid Frank Kamahele was at Pahoa High School, a new teacher came from Texas and became the basketball coach. Frank loved basketball, and the new coach helped him to go to the University of Hawai‘i on a scholarship to play basketball. It so happened that the University of Hawai‘i had an Air Force ROTC program, which Frank joined.

Upon graduating, Frank applied to go to flight school. They told him to go home and wait for an opening, and one came a few months later. Next thing he knew, he was in Arizona at flight school.

‘Luckiest person in the world’

Frank told me recently that he feels like the luckiest person in the world. He came from a very poor family, and no one in the family had gone to college. If it hadn’t been for the planes flying overhead and a kind, dedicated teacher from Texas, his career might have been “cut cane man.” He was pretty good at that and earned $200 a month for contract cane cutting. At that time, it was a lot of money.

Frank was cool-headed. He told me about the worse thing that happened to him during his flying career. It happened at Honolulu International Airport once when he was taking off: when he was around 150 feet in the air, an engine fell off. He was piloting a KC135 refueling tanker –- a flying bomb the size of a Boeing 707.

He said the Control Tower called and asked: “Do you realize you lost engine number four?”

“Roger,” Frank replied.

“I repeat – do you realize that you lost engine number four?”

“Roger.” That was the extent of his conversation with the Tower. In the meantime, Frank shut off the engine, the fuel, etc. He did not want a fire to start.

It happened that he was on his routine annual check ride, so an Air Force inspector was along for the ride and sitting in the jump seat. Except for the engine falling off, everything was going well. The plane flew on three engines, no problem.

Frank Kamahele gets back on the horse

Once they stabilized at altitude, Frank requested permission to land and get another plane to finish his mission. He knew things were going smoothly and that he needed to get his crew back up in the air again to keep up everyone’s confidence. When they landed uneventfully, he asked the flight inspector if he wanted to go back up with them.

The inspector told him: “I’m sure you all will do just fine.” He could not wait to get off that plane and on the ground.

After his career in the Air Force, Frank returned to the Big Island and flew a 6-passenger tourist tour plane. He told me he could not keep on doing that because it was too boring and uneventful.

So he went to O‘ahu to work at the airport as an administrator, and the Hilo/Kona airports manager job came up. He flew back to Hilo and applied for the job, which he kept for 17 years.

This is an example of how you just never know what has an influence on a young kid and might change his or her entire life for the better. It convinces me that the $1 million annual TMT contribution toward the Big Island’s K-12 education will be so valuable to our children.

See also:

Maku‘u Stories, Part 1: My Kamahele Family in Maku’u

Kamahele Family of Makuu, Puna, Hawaii

I’ve been talking with my extended Kamahele family over on my Facebook page. It’s got me thinking about our Kamahele family of Makuu and how it was back then.

I’m going to rerun five posts I wrote back in 2009 about life in Maku‘u and my family there. Every Monday I’ll post another one, and here is the first.

My Kamahele Family in Maku‘u

Today I was thinking about my Kamahele family and especially my grandmother Leihulu’s brother, Ulrich Kamahele.

Everybody knew him as Uncle Sonny, as if there was only one “Uncle Sonny” in all of Hawai‘i. He was a larger-than-life character. In a crowd, he dominated by the sheer force of his personality. Since I have been thinking about him, I thought I would write a several-part story about Maku‘u.

My extended Kamahele family came from Maku‘u. When we were small kids, Pop took us in his ‘51 Chevy to visit.

He turned left just past the heart of Pahoa town, where the barbershop is today. We drove down that road until he hit the railroad tracks, and then turned left on the old railroad grade back toward Hilo. A few miles down the railroad grading was the old Maku‘u station. It was an old wooden shack with bench seats, as I recall. That is where the train stopped in the old days. A road wound around the pahoehoe lava flow all the way down the beach to Maku‘u. That was before there were the Paradise Park or Hawaiian Beaches subdivisions.

We did not know there was a district called Maku‘u; we thought the family compound was named Maku‘u. Of the 20-acre property, maybe 10 acres consisted of a kipuka where the soil was ten feet deep. The 10 acres on the Hilo side were typical pahoehoe lava. The property had a long oceanfront with a coconut grove running the length of the oceanfront. It was maybe 30 trees deep and 50 feet tall.

The old-style, two-story house sat on the edge of a slope just behind the coconut grove. If I recall correctly, it had a red roof and green walls. Instead of concrete blocks as supports for the posts, they used big rocks from down the beach.

There was no telephone, no electricity and no running water. So when we arrived it was a special occasion. We kids never, ever got as welcome a reception as we got whenever we went to Maku‘u.

Tutu Lady

The person who was always happiest to see us small kids was tutu lady Meleana, my grandma Leihulu’s mom. She was a tiny, gentle woman, maybe 100 pounds, but very much the matriarch of the family. She spoke very little English but it was never an issue. We communicated just fine.

We could not wait to go down the beach. Once she took us kids to catch ‘ohua—baby manini. She used a net with coconut leaves as handles that she used to herd the fish into the net. I don’t recall how she dried it, but I remember how we used to stick our hands in a jar to eat one at a time. They were good.

She would get a few ‘opihi and a few haukeuke and we spent a lot of time poking around looking at this sea creature and that.

Between the ocean in the front and the taro patch, ulu trees, bananas and pig pen in the back, there was no problem about food. I know how Hawaiians could be self-sufficient because I saw it in action.

The house was full of rolls of stripped lauhala leaves. There were several lauhala trees and one was a variegated type. I don’t recall if they used it for lauhala mats but it dominated the road to the house.

There were lauhala mats all over the place, four and five thick. There was a redwood water tank, and a Bull Durham bag hung on the kitchen water pipe as a filter.

Years later when I showed interest in playing slack key, I was given Tutu’s old Martin guitar.

She played it so often that the bottom frets had indentations in it where her fingers went.

Making Life Better, Part 2: Hawaii in the Information Age

Consider how history has impacted us here in Hawai’i:

Around 1000 AD, people were sailing back and forth to Hawaii. At the same time, the Crusades were taking place. Around the time Captain Cook arrives, in 1778, the Declaration of Independence has just been written.

By 1860, the Pony Express was delivering mail from New York to San Francisco in 10 days.

In 1908, Ikua Purdy, Archie Kaaua and Ben Low take the top award at the Cheyenne Rodeo – the pinnacle of rodeo competitions in the world.

In 1952, KGMB was the first TV station in Hawaii.

In 1989, Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web.

In 2010, the “like” button was added to Facebook.

This timeline gives us a hint of how much Hawai‘i and its people have assimilated into the world around us.

This is not a bad thing. This country elected someone who grew up here as President of the United States. We enjoy our iPhones.

Our young folks under the age of 20 or so don’t remember a time before we pressed electronic buttons.

The Information Age

We are in an information age; an electronic one. It’s an age of learning by doing, which is what Hawaiian have done for eons. And it’s exactly what our group PUEO (it’s short for Perpetuating Unique Educational Opportunities) is reaching for.

When my friend Rick Blangiardi, general manager of Hawaii News Now (HNN), spoke at the Hawai‘i Island Economic Development Board’s annual meeting he gave an impressive talk about the history, as well as the future, of HNN under his leadership.

He said the most impactful thing to happen to the news industry was, “This.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out his iPhone.

Shortly after that, there was a stand-off on Maunakea about building the Thirty Meter Telescope. Movie stars and sports heroes jumped on board and the story went viral.

Welcome to the world of real time news and to the Information Age. There’s no backing away now. We cannot pick and choose in which areas we interact with the world, or hide as though there are no outside forces affecting our lives here in Hawaii’i.

We’re all still adjusting, but this is a good thing. We aren’t only taking in information. We have something that is unique to the core of Hawai‘i, our aloha, that we can share instantaneously as well.

photo: Calerusnak at English Wikipedia

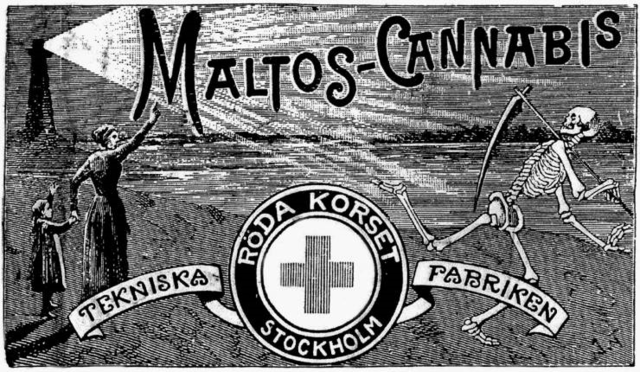

The History of Medical Cannabis

Take away all the politics and cannabis is just another plant. The history of cannabis being used medically is extensive, though; people have used it for its medicinal qualities for thousands of years.

So what’s the difference between “cannabis” and “marijuana?”

“Cannabis” is an old word. It’s the name of the genus of the flowering plant that is indigenous to Central and South Asia, and the Greek, Persian and Hebrew languages all have variants of it.

The more recent term “marijuana,” a word used more commonly in the U.S., probably derives from slang. The 1937 U.S. Marihuana Tax Act legitimized the word.

Whatever you call it, the history of cannabis use, both for medicine and ritual, goes back thousands of years.

Ancient History of Cannabis

In around 2700 BC, the Chinese Emperor Shen Nung was prescribing cannabis tea to treat gout, rheumatism, malaria, and poor memory. Hindus in India and Nepal used it thousands of years ago. Ancient Assyrians used it in religious ceremonies.

Just twelve years ago, in China, archaeologists found a leather basket full of cannabis leaf fragments and seeds next to a mummified shaman they dated at around 2,500 to 2,800 years old. There’s evidence of cannabis use in Egyptians mummies that lived in around 950 BC.

And the South African Journal of Science says that, more recently, pipes dug up from William Shakespeare’s garden in Stratford-upon-Avon contained cannabis.

Jim Berg, M.D., who has offices in Kona, Ocean View and Hilo, is physician to about half the Big Island patients with medical marijuana cards. He says the ancient Chinese used cannabis for what they called “unsettled spirit.”

Long Ago Experts

“The Chinese had some interesting ways of calling schizophrenia and bipolar, mental illness, ‘unsettled spirit,’” he says. “So cannabis would settle the spirit and help calm people down, and help them get better sleep.

“The Chinese really had some interesting names. Like they said that hot phlegm obscured the portals of the mind. They used cannabis to clear the hot phlegm and to clear the portals.”

He says that by the time of Huangi, the “Yellow Emperor” of China who reigned from about 2697 to 2597 BC, “they had a very sophisticated system and their pharmacy was actually quite advanced.

“I would put their pharmacists up against our pharmacists any day, because we’re scientifically based but they were practically based. They would go pick their plants. They would have to prepare all their medicines and use them, and then they would get the direct feedback from the people.” The history of cannabis, he says, includes its use for childbirth in the Middle East.

In America

In 1619, King James I decreed that every colonist in the Virginia Company grow 100 hemp plants. Hemp is a non-psychoactive variety of the Cannabis sativa plant. Its fibers made rope, sails and clothes. Hemp was legal tender in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland.

Cannabis was used extensively in medicines and was extremely commonplace in the U.S. between 1850 and 1937, says Berg. “We have well-documented use of it being used by doctors then,” he says. “In fact, we can easily say it was the most prescribed medicine in this country for people before 1937.”

“It was used for sedation and as an anesthetic for doing basic procedures. It was used for depression, and it was used, most importantly, for sleep. It was in sleep tonics. It was in pain medicines. I think sleep and pain are probably the most traditional reasons cannabis were used over the years in this country – people trying to deal with their pain issues.

“And this is all stuff that was totally legal at the time. People could just buy from the guy down the street, or the guy in the wagon. Of course, there were probably many people who got addicted to the opiate in it. That was probably why it got to be such a big seller.”

Cannabis was mixed with other herbs, and often with opiates.

“Eventually, both the opiates and the cannabis became illegal, but until then they were used by moms and pops, by kids. It was in cough syrups. It was in good, old-fashioned tonics, just to help you feel better.”

Government Changes

When the U.S. Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, there was suddenly an excise tax on cannabis. People could only use it for authorized medical and industrial uses.

In 1970, the Controlled Substances Act passed, replacing the 1937 Tax Act. That’s when drugs were classified into different schedules for the first time. Cannabis and some other drugs became “Schedule 1.” This meant they had a high potential for abuse, had no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and there was a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision. It became illegal at the federal level to use a Schedule I substance.

(However, a synthetically prepared type of cannabis, Marinol, is commonly used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy and appetite loss caused by AIDS. It went on the Schedule III controlled substances list.)

Eye-Opening

It was significant to the way many Americans view medical marijuana, says Berg, when neurosurgeon Sanjay Gupta went on CNN a couple years ago. He did a series of investigations about cannabis and its medical properties. Among other things, he showed kids with seizures treated with cannabis that has high-dose CBD (the compound with medical benefits) and low-THC (the psychoactive part). Their seizures responded remarkably.

For instance, a young girl named Charlotte went from having 300 seizures a week, some of them two to four hours long, to just one or two a month.

“There is now promising research into the use of marijuana that could impact tens of thousands of children and adults,” writes Gupta, “including treatment for cancer, epilepsy and Alzheimer’s, to name a few. With regard to pain alone, marijuana could greatly reduce the demand for narcotics and simultaneously decrease the number of accidental painkiller overdoses, which are the greatest cause of preventable death in this country.”

Hawaii’s legislature voted to make medical marijuana legal in 1999. This change took effect in 2000.

Is Mauna Kea Really Sacred?

Peter Apo, Office of Hawaiian Affairs trustee, recently talked about something that really struck me: He said the claim that the whole of Mauna Kea is sacred cannot be validated.

One thing that had been puzzling him, he says, is that in previous cultural clashes here in Hawai‘i, scholars always participated – but this time they were silent.

“With the TMT, there was this tremendous silence,” he said. “No one was speaking out.” So, he said, he did his own research, consulting with 12 or 13 leading scholars on the topic.

Cultural claims, he said, are validated three ways: by archaeology, oral tradition (“such as the Kumulipo”), or through present-day scholars.

“And the litmus test is there has to be a historical basis for that belief system or practice,” he said. “You have to show it was exercised in the past. And you have to have a pattern of frequency. None of that was present, at least in my foray in the research.”

“Long story short,” he says, “the claim [of the entire mountain being sacred] could not be validated.”

He write about this in more detail at Let There Be Light on the TMT at Civil Beat:

This research has led me to some conclusions. First, there are indeed places on Mauna Kea that are sacred. These are places where Hawaiians have continuously participated in traditional and customary practices; so there are unquestionably specific geo-cultural sites on Mauna Kea that are protected, and the practices that are associated with these sites meet all the defining criteria of being traditional and customary.

But the extension of sacredness to the entire mountain and the air column above it gives rise to questions about how much cultural validation there is for the idea that this pre-empts any and all other uses of the mountain.

I found no documentation indicating that Mauna Kea, as a whole, is sacred. I could not find any reference to any blanket of sacredness over the entire mountain and the air column in any of the usual sources of validation — not even in the Kumulipo Hawaiian creation-origin chant, or in the writings of Native Hawaiian historians of the 19th century like Samuel Kamakau, David Malo, John Papa ‘I‘i and Kepelino.

Beyond the blanket-of-sacredness claim, there is nothing else on record to suggest any validated sacred places would be disturbed by the construction or operation of the TMT.

Validated sacred places include the peaks of Pu‘u o Kūkahau‘ula, Pu‘u Poli‘ahu and Pu‘u Lilinoe, Lake Waiau, and various heiau (temples), ‘ahu (altars), ana (caves), lua kā ko‘i (quarries), and ilina (burials).

In fact, I believe the decision about the TMT’s location was made to ensure that no sacred site was violated, nor access to any sacred site impeded. The telescope was also sited below the summit to minimize its visual obtrusiveness. Read the rest

This rings very true to me.

My Pop helped to bulldoze the road to the summit of Mauna Kea back in about 1964, and when I think back to that time, none of my Hawaiian relatives at Maku‘u ever said one word against it. No one ever even hinted it was against religious and cultural practices. I don’t remember our relatives ever telling us that the mountain was forbidden territory.

Pop was proud of what he was doing, and my brother Robert used to fuel up and service his bulldozer.

See the name at the top of the TD 30? That’s my dad. (I’m a junior.) This picture of my Pop operating his bulldozer on the summit of Mauna Kea is from a PBS clip that you can see here.

There was no mention of anyone up on the mountain protesting when Pop was building the road, because there wasn’t anybody protesting. There was never any feeling he was doing anything against the culture. There was no discussion about it, period.

Peter Apo said something that makes so much sense to me:

“The TMT presents probably the greatest opportunity – the greatest cultural opportunity, religious opportunity – that we will ever have to do the one thing that is at the center of every cultural group. That is, search for the ancestors. Our story of creation begins with the night of Pō, with the darkness. I’m assuming that at some point in time, with projects like the TMT, we will actually be able to go back and find the Night of Pō. I cannot think of anything more significant than that.”

I agree, and I don’t think it was a bad thing that Pop helped build that road. We humans are always trying to climb up to the top of a mountain to see what’s on the other side. I’m curious to see back in time.

My concern is that we are shutting off the opportunity to possibly learn the answer to the greatest question mankind ever asked: “I wonder what’s on the other side?”

Honoring Their Memories

We were so young. I was 25 and I was actually one of the older soldiers, because I went to Officer Candidate School.

We were so young. I was 25 and I was actually one of the older soldiers, because I went to Officer Candidate School.

That year changed me forever. The unspoken rule was that we all came back or nobody came back. Everybody came back from Vietnam, but some didn’t come back alive. This is where I learned that it’s about all of us, not just a few of us.

It is in honor of their memories that I believe in the rule of law of the U.S. Government.